Reflections and Speeches

Tomas Bata

Translation by Otilia M. Kabesova

Foreword

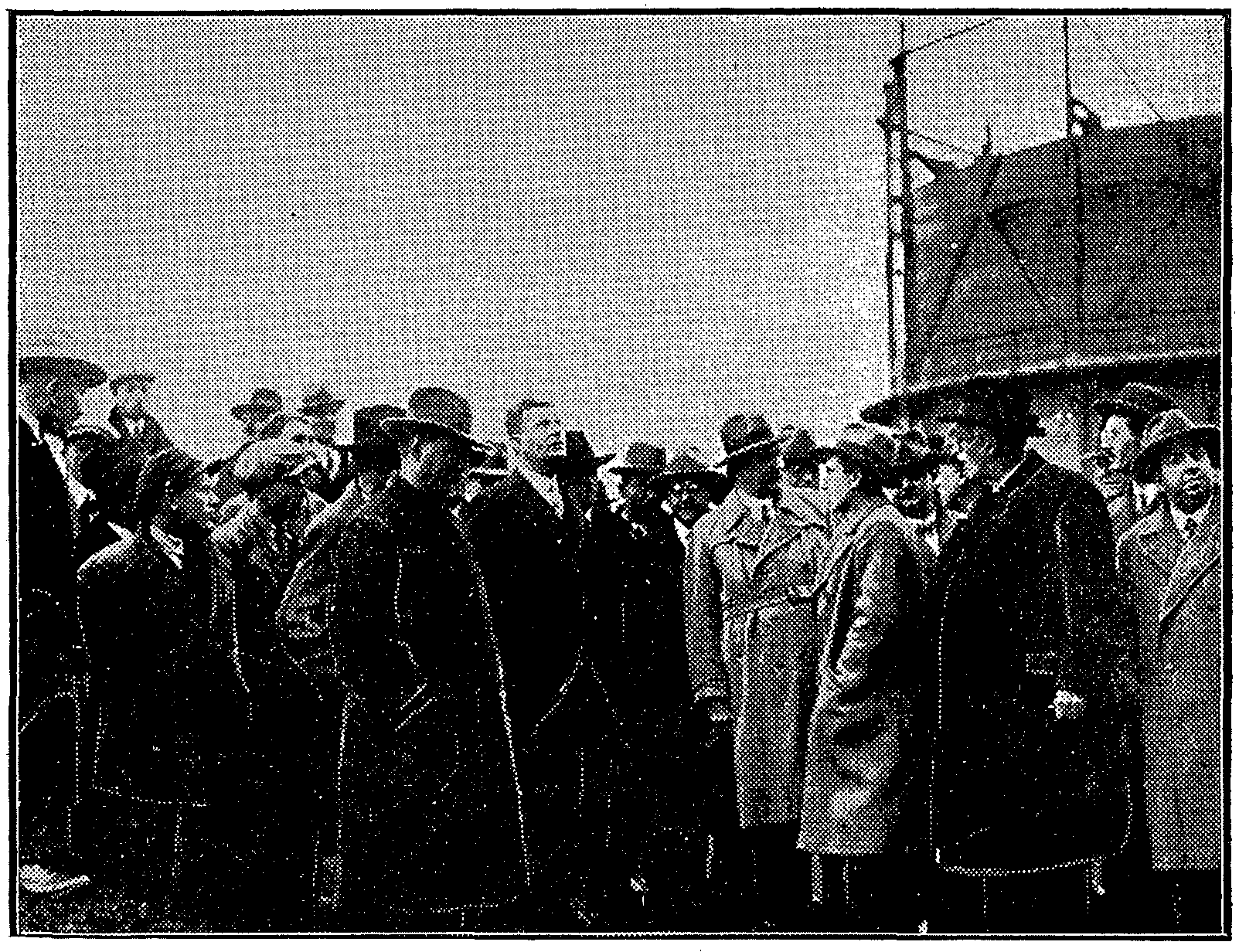

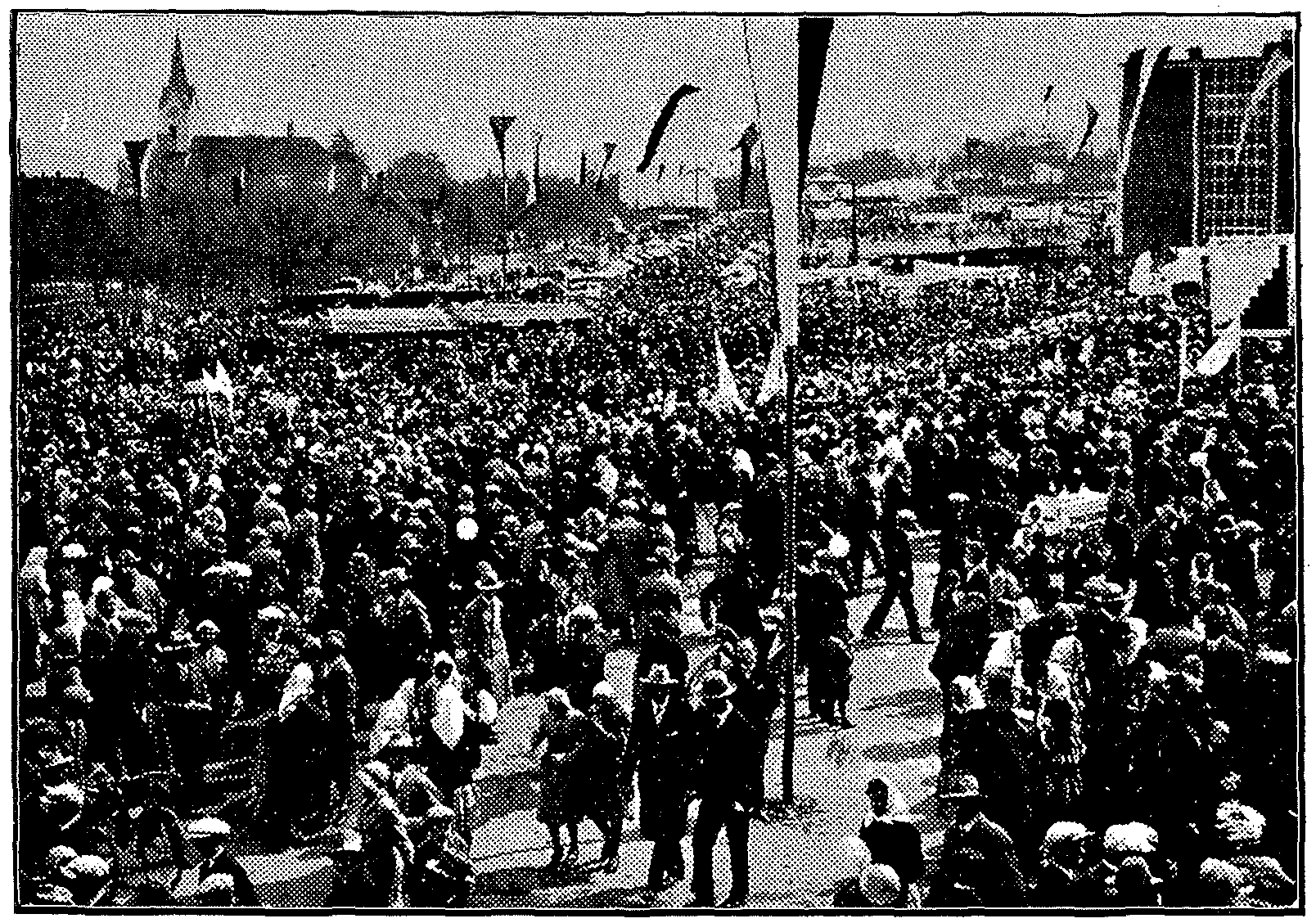

We can see him in front of us in the middle of a crowd of men with rough, determined faces and work-worn hands - in the midst of cobblers, tanners, salesmen, engineers, masons, brick-makers, road-menders, carpenters, farmers and almost all the occupations where man handles with his hands, struggles with it, kneads it and works it until he transforms it into a piece of bread for himself and a benefit for others.

We can see him, a man among men, proudly and arduously coping with the difficulties of their jobs, searching for ways and words, attacking encouraging, providing strength, enthusiasm, determination and faith.

We can see him in the midst of teachers, physicians, chemists and other intellectuals - listening intently with a hidden fire in his half-closed blue-gray eyes, and seizing the heart of the matter and people in a single sally.

And we can also see him bent over small pieces of paper, carefully, honestly and thoroughly weighing each word, playing with it, polishing it and testing its impact on the hearts and souls of people he has to win over for actions he saw and believed in himself in the first place.

There was something apostolic in the man standing astride of the ages with all the tenacity and ambition of his virile intelligence; he never sidestepped a problem but found pleasure and reward in solving it.

His faith in people and their common sense was captivating; and just as captivating by its simplicity was his way of expressing his ideas.

We consider it our duty to preserve the spiritual legacy of Tomas Bata, as it appears in his reflections and thoughts. We are convinced that we will thus set an example not only to ourselves, but also to those who, burdened by their own work and difficulties, are searching for an example to follow.

These are not academic or theoretical reflections of an economist, sociologist, philosopher or politician, allowed to use freely his phantasy and to let his thoughts and beliefs create an artificial, closed world without any responsibility whatsoever to the real world.

These are speeches of a man whose words were followed by deeds; they cannot, therefore, be separated from his work. He will, undoubtedly, be best understood by those who, while accomplishing their daily work feel that nothing living is ever finished and that life may be grasped in the infinity of gestation, birth and aspiration, exactly as it was understood and lived by Tomas Bata.

A.C.

Our life is the only thing in the world we cannot consider as our private property, as we have not contributed to its generation. It was only loaned to us with the obligation to pass it on to posterity improved and augmented.

Our contemporaries, but particularly our posterity have therefore the right to demand that we render account for our life. This book should serve as such an account.

Tomas Bata

Table of Contents

Foreword (Prof. Milan Zeleny)

Introduction to English Translation of "Reflections and Speeches" (Thomas J. Bata)

The Historical Example of Thomas Bata

(Foreword to the Second Czech Edition by Antonin Cekota)

Chapter I.

My Beginnings: On My Own - My Adolescent Dream About Gentlemen - How I Became Friend with Machines - How I Became Entrepreneur - The Time of Searching - How Was the First Military Order Received in Zlin - How Tomas Bata Perceived the Problem of 1918 - Enthusiasm - Collaborators - Heat - Bad Times -Factory Lunches - To My Collaborators! - To Our Public - Friends! - The Road to Improvement - The Speech of the Boss to the Participants of a Competition in Cutting on September 17, 1922 - Collaborators! - Holidays - The Profit Sharing of Workers - Autonomy of the Workshops

Chapter II.

The Organizer: Awakened Forces - The Fundaments of Self-Management - Obstacles to Self-Management - Education to Affluence - Parents and Children - Business and Confidence - Open Accounting - Self-Management of the Workshops -Self-Management in Practice - Management of the Enterprise - Planned Economy - Planning - Education to Leadership - A Perfect Machine - Concentration - Our Dining Room - Labor Regulations - Study of Mathematics

Chapter III.

The Industrial Manager: Freedom of Trade - What do I Wish to Our Business? -Technical and Organizational Progress in the Production - Obstacles to Progress in Production - Cheating in Business - Bata's Views on Transportation - Why to Spend 10 Billion Crowns on Road Construction? - Transportation, Roads and People - My Economic Philosophy - Friendship in Holland and in Our Country

Chapter IV.

The Educator: The Object of Schools - The Purpose of Education - Training in Economic Management - School and Family - Remarks on School Reform - Savings-Management - Property and Knowledge - Speech to Engineering Apprentices - The Evening Business School - The Business School - Construction, Education, Housing - The School for Young Men - New Education - To Young Men About to Choose Their Career - Young Men! - The Road to Honor, Power and Wealth -Personal Discipline and Improvement - How to Become an International Entrepreneur - Let us Learn from the Best - Sense of Enterprising and Work - Health and Peace Through Self-Discipline

Chapter V.

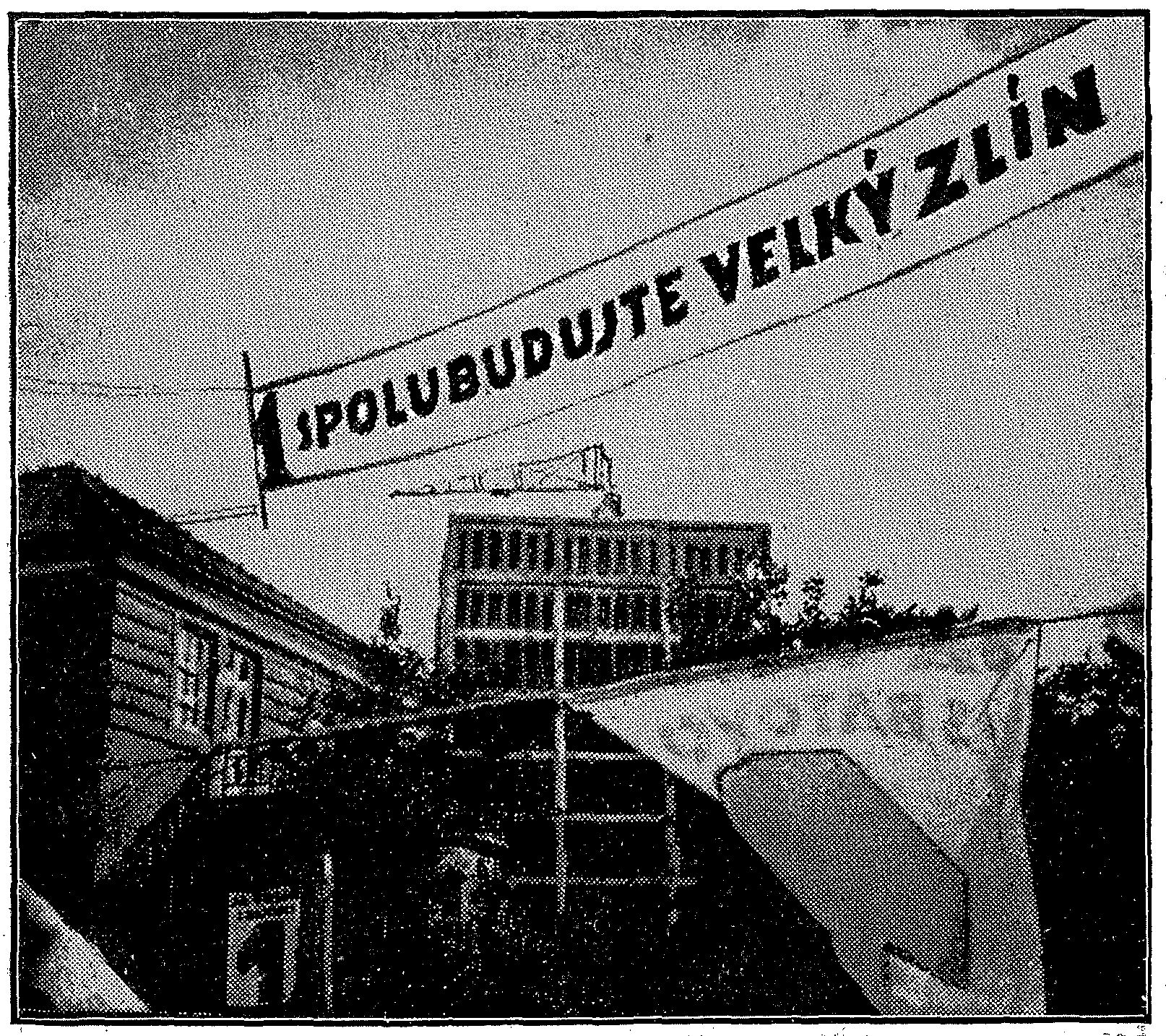

The Citizen: Communal Elections in Zlin in 1923 - Our Enterprise and the Town of Zlin - Friends! - Our Work Program - Greater Zlin - The Municipal Elections of 1927 - More Confidence - Cooperation Between Industry and Agriculture - Our Needs and Agriculture - The New Agricultural Production - New Thinking - Our New Work Program - The Growth of Business and Crafts in Zlin - The Trade Question - The Zlin of Old - Citizens - Why a Greater Zlin? - My Goal - How I Look at Our Municipal Government

Chapter VI.

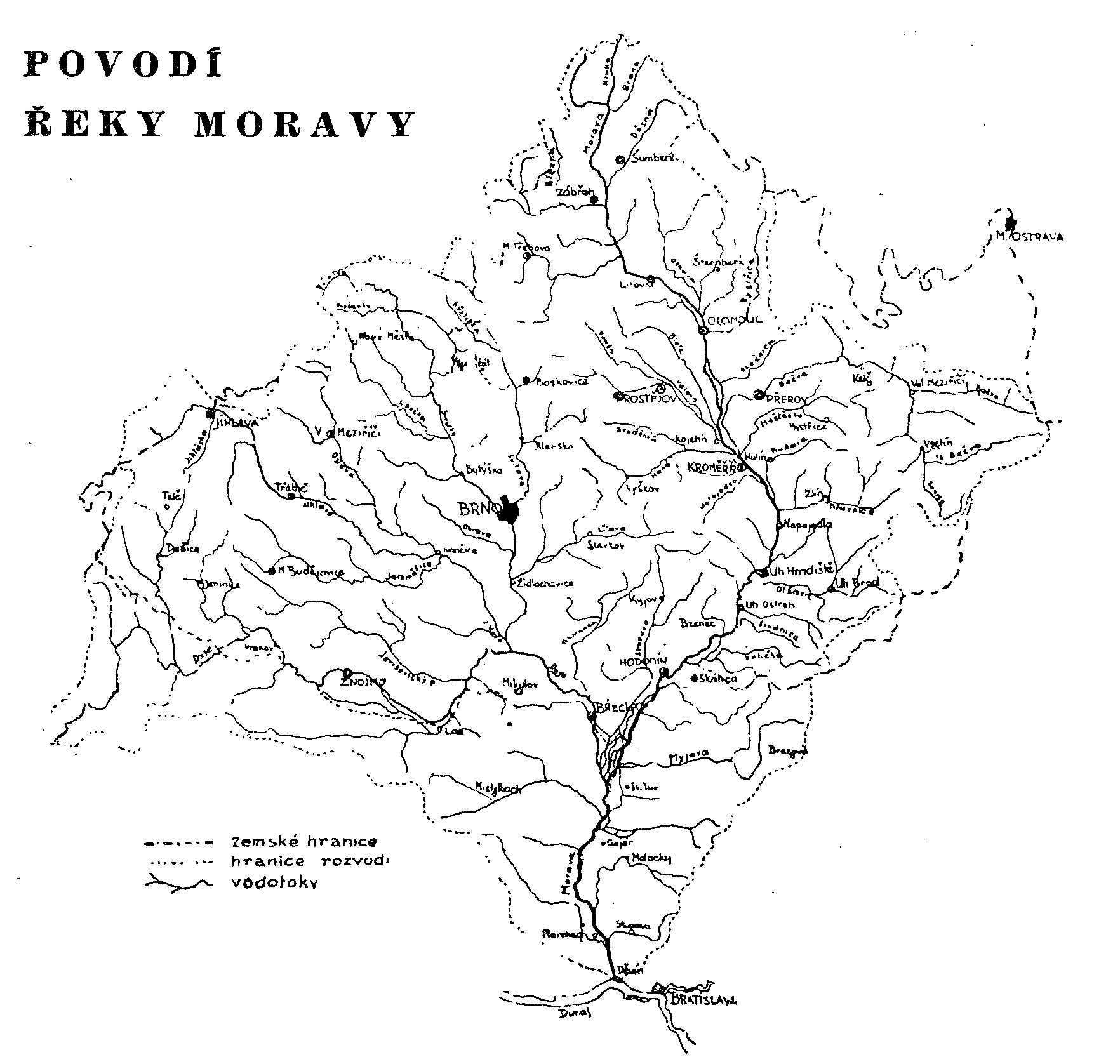

The Statesman: Public Accounting - The Land Budget and Investments - Project of the Organization of Land Finances - My Donation for the Acquisition of Telephones - Why Do I Oppose a Land Loan Issue for 250 Million Kc - The Main Problems of Land Economic Management - The Value of Civic Honor - The Regulation of the Management of Moravian Waterways - Moravians! - Project

Chapter VII.

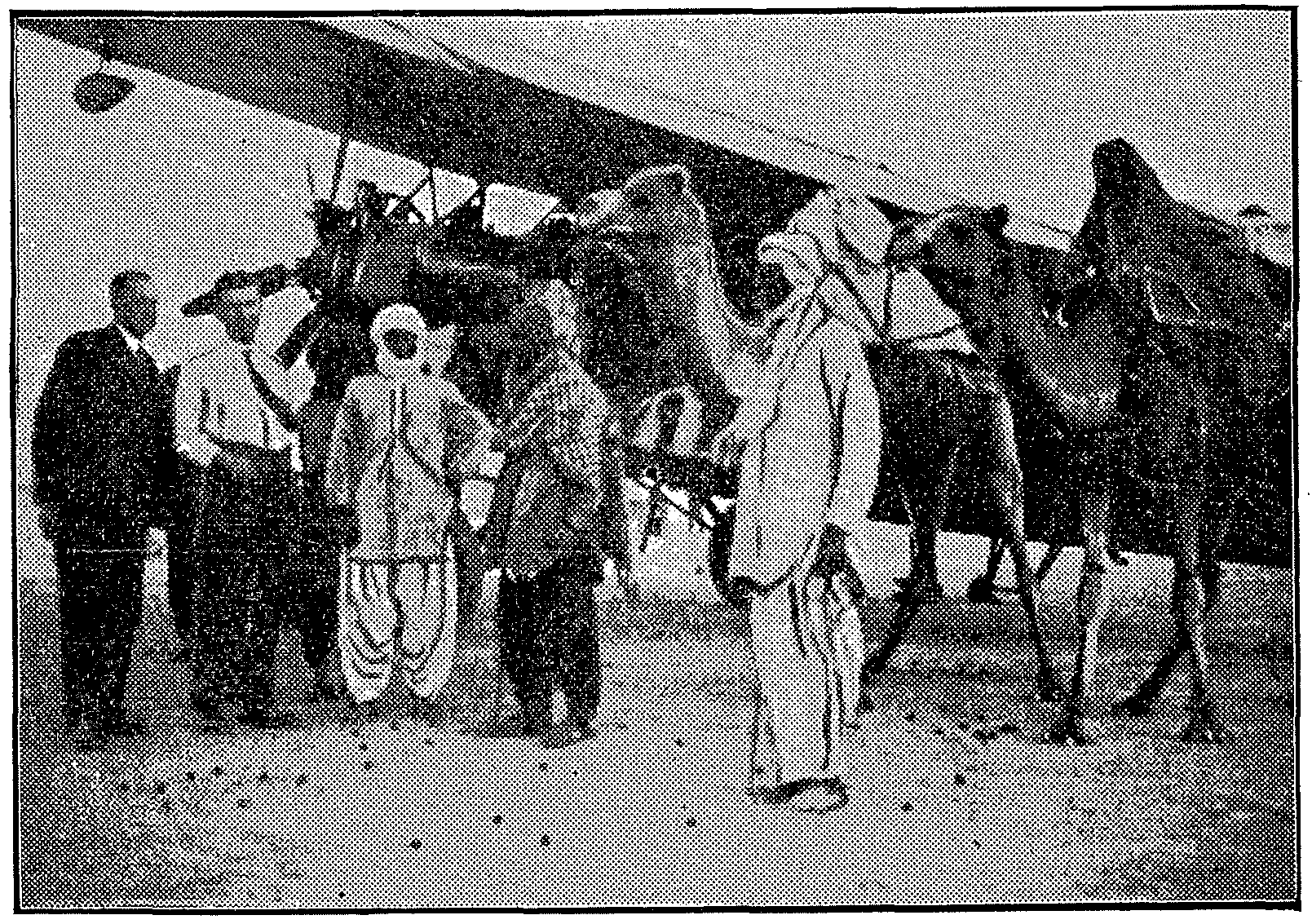

The Pioneer: The First Trip to India in 1925 - From Holland - America-Europe -The Flight to India in 1931 - The First Day of the Airtrip - Aviation and Human Interdependence - Christmas over the Desert - The Future of the Desert - The Journey from Egypt to Palestine - From Bushire to Beludshistan - Fleeing a Storm - Taurus - From the Indian Notebook - After Return

Chapter VIII.

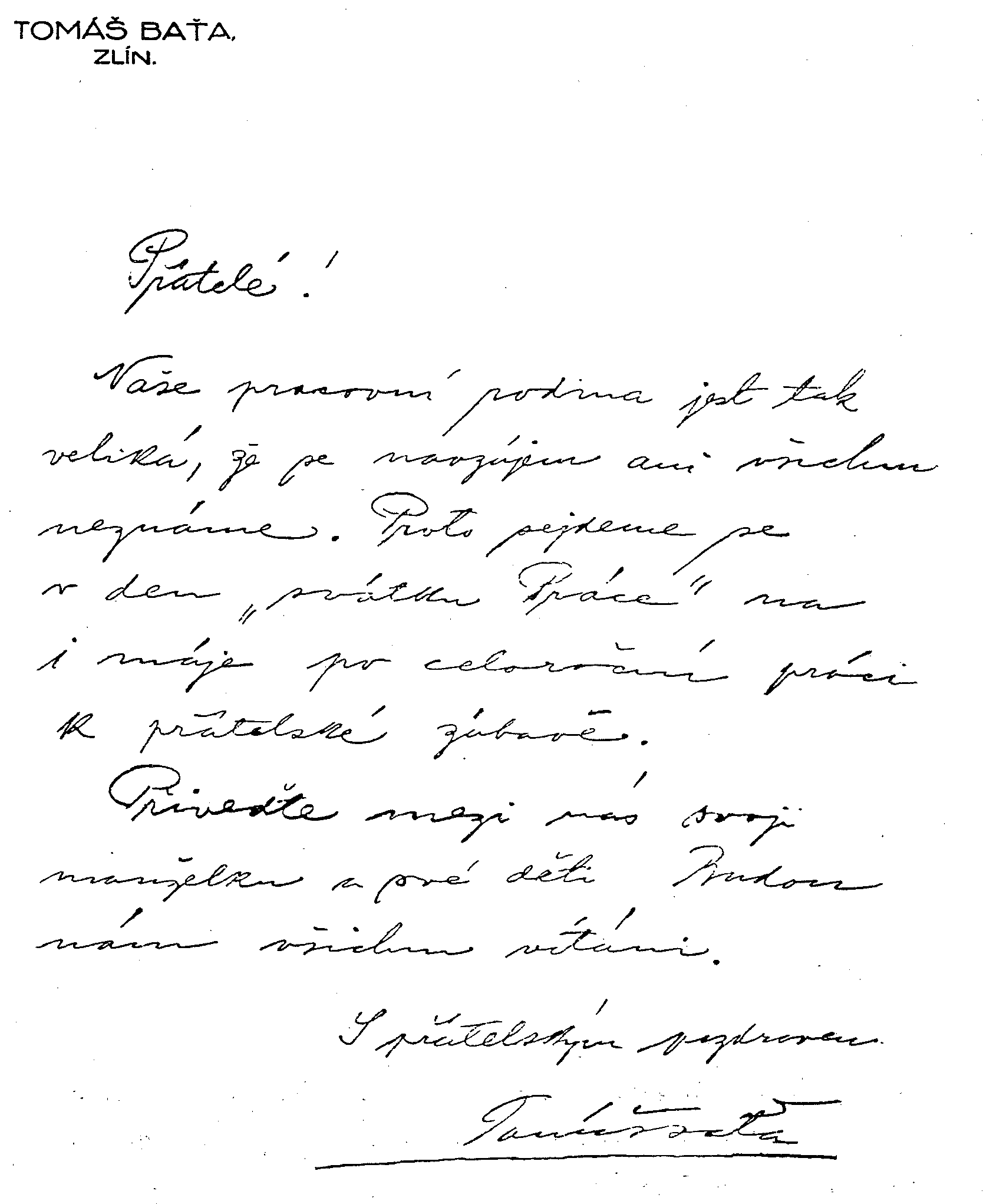

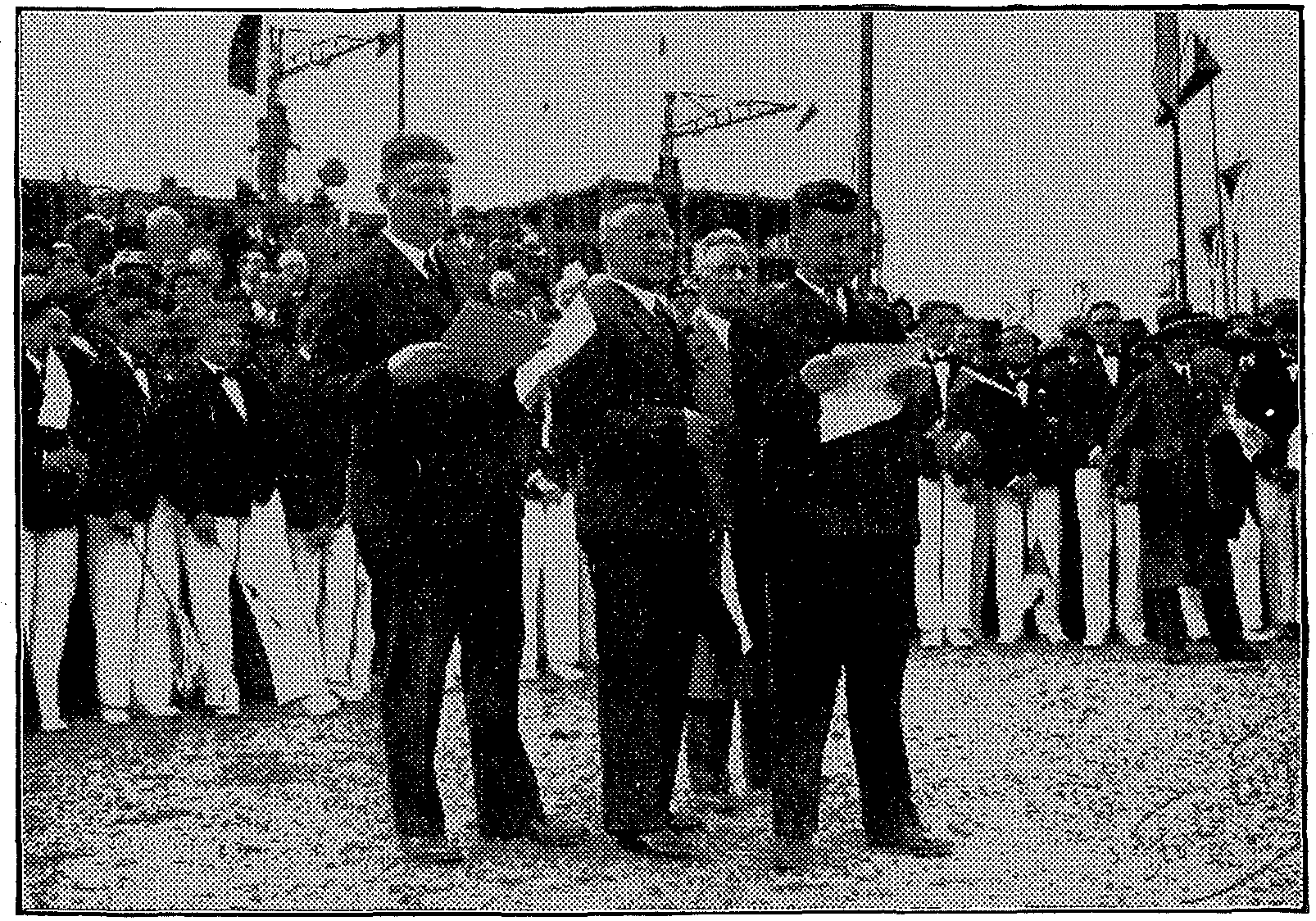

The Collaborator: Labor Day Holiday - Labor Day Speeches, 1924-1932: Collaborators! - Friends! - Friends and Collaborators - My Collaborators-Our Dear Guests - The Guilt is Primarily Mine - Friends! - My Collaborators, Our Dear Guests -Friends and Collaborators - The Last Labor Day of Tomas Bata - The English Way in Comparison With Our - Financial Reconstruction of Banks - Enough Money But Little Trust - Correspondence - Leaving the Job-Failure at Work-Firing - Defender - New Production Trends - The Falsified Certificate of Proficiency -My Reply - The Anti-Bata Congress of Shoemakers in Brno - To the National Shoemakers' Congress in Prague - My Recollections - Open Letter

Chapter IX.

The Man: My Relationship to Work - Bata and Edison - Funeral Observance for Thomas Alva Edison in Zlin - The Duties of Leaders - The Method of Justice -Americanism - Cold - Mountains - Heroism - Machines and People - Problems with Using Machines - The Successor Problem - The Last Message - The Forest Cemetery in Zlin - The Personality of Tomas Bata and His Family - The Batas-Shoemakers for 300 Years - The Work Continues

My first skill which I remember was a prayer. My pious mother taught me the "Our Father" very early, together with "Hail Mary" and "I Believe in God". I often had to demonstrate my arts to visitors and it rarely happened that I would not receive a kreuzer for my efforts.

When I was six, I started making shoes from worthless leather cuttings, stretching them over that lasts of my own making. From such cuttings one could produce shoes about as big a thumb, but they were shoes nevertheless and they were in demand by the admirers of the youthful "entrepreneurship".

One pair of such shoes required a full day of diligent work. Their price fluctuated between 4 to 10 kreuzers. This was a pretty good reward if we consider that the value of four kreuzers was a "fourther" - a coin from pure copper of the size of today's crown. The value of 10 kreuzers represented a "sixer" - made of pure silver, of the size of today's twenty-heller.

Before the Easter holidays, together with the other boys from our area, I took part in the collective enterprise called "rattling".

We elected our "boss". Those who did not come on time were given a mark. One mark represented a penalty of one kreuzer.

I did not want to get a mark. For the morning rattling my brother and I used to wake up at four o'clock, but rarely did we manage to catch up with the boys at our gathering place. So, there was always plenty of "marks".

Each day I added up our treasurer's income and before starting the division I had all the earnings added and multiplied and the total divided by the number of rattlers. However, the "boss" and his treasurers arrived at a different count.

According to their count, everybody should have barely a half of what was due.

Bitterness, anger and even revolt which such injustices inspired in me cannot be measured.

I asked my father for help, but he declared that this is how the world works and he preferred to pay his money for the losses I suffered. He shared only in my sorrow over the human wickedness. At that time I already became distrustful of cooperatives.

When I was allowed to go to fairs, the circle of my enterprises started to widen considerably.

At the beginning I provided only assorted services to the merchants: helping them in and out of their boots, carrying their shoes - that sort of thing. Such services were paid mostly in the form of "drink money". My rewards started at zero and ended at about two kreuzers level.

All such earnings I saved at the post office. The money was deposited in the following way: one bought postage stamps for five kreuzers each and pasted them on a card. When there was ten stamps on the card, the postmaster entered the deposit in the saving book.

Antonin Bata, Tomas Bata's father, * 1.8. 1844 in Zlin - † 5.9. 1905

When I was ten, my mother died. With her I lost not only the solicitous mother's care, but that of my father's as well. Two years later we moved from Zlin to Uherske Hradiste.

My father was born entrepreneur. He was attracted to everything demanding courage - but he lacked persistence. The first obstacle he encountered spoiled his appetite for the old and instilled his hope for some new project.

My father was a smoker and he used to meet with his neighbors in the tavern. In those days sitting in the pub and smoking were inseparably associated with the concept of manliness. Yet, he always cautioned us to avoid the weakness of smoking. Because he knew that words were to weak to keep human wants under control, he guided our education with great ingenuity by deeds, work and enterprising. First he gave us the opportunity or he showed us how to make money - then he allowed us to keep our earnings. In this way he suppressed the intensity of our desires and taught us the tending of capital.

Both my and brother's life were closely interconnected with our father's business. When business was good we had enough to eat, when it went badly- there was hunger.

At twelve I understood quite clearly what had to be done in order to avoid hunger. At fourteen I had the whole sales part in my own hands: it meant that I already held the hunger firmly by its horns.

I completed the four-year public school in Zlin. At the beginning of my fifth year we moved with our parent to Uherske Hradiste and I entered the German school there: there was none other. Only few pupils actually knew German - I did not know any. The classes in Zlin were in Czech. My school attendance was poor because I was needed for watching.

I neglected the first two month of school and that of course detracted from my further schooling because I missed the beginning. In spite of everything, my older brother Antonin managed to get very good grades at this school.

In Uherske Hradiste I did not learn anything and the little I brought with me from Zlin - I almost entirely forgot.

Our father did respect education, but it was often necessary to put business before school. There were no books or newspapers at our home, with the exception of farmer's almanac which was needed around because of the county fairs. Businessmen then considered books and newspapers a luxury, suitable perhaps for the gentlemen.

When I reached fourteen, I dropped out of the school and entered the apprenticeship at my father's. At this time I also met with my first book which contained something else than the almanacs.

One day the son of our journeyman Sirocka brought us "The Pictorial History of the Czech Nation".

Although I liked books, the best school of my life was my employment. My father could expand the shop very soon because I managed to sell our products at fairs in surrounding towns. Now we started to have plenty of everything and most of all money.

My father bought the raw material on credit from Koditsch & Co. in Vienna. The money he took in he deposited in silver guldens in our armoire. My self-confidence grew together with my success at work. One day I determined that I am not sufficiently recognized: the journeymen did not want to unlearn their boxing of my years and even father was not appreciative of my work. I decided to stand up on my own feet.

I asked my father to pay me the dowry of 200 guldens, inherited from my mother, which he had arranged to redeem from the orphan's trust when we ran into some very bad times. But my father wisely ignored my request. So I left without money. I settled down in Vienna where my sister Anna worked as a servant at the time. She contributed thirty guldens to my "small capital", I supplied the élan of my youth and I started on my own. I set up a small workshop at my relatives in Döbling.

I started with mikado-shoes. That was my misfortune. My father started producing this kind of footwear shortly before my departure with big hopes for the future but without any experience. I took over both his hopes and his ignorance and in addition started the business from the wrong end. Instead of selling a part of produced goods first and then continued with the production, I sinked my entire capital into the first production.

I did not know the language and I did not know the market. Finished goods I could not sell because they did not satisfy the requirements of the market. Fortunately, my father was out looking for me. He needed me. My cousin explained that I cannot work without a "card" and that police had already inquired about me: I have to go to Hradiste to apply for my trade permit. So I went back to Hradiste and there I remained.

After coming back to my father I took charge of the sales again. But I did not like the selling at fairs anymore. I saw too many disadvantages in it. So I listened very carefully when market men talked about delivering their goods to Prague. I brought a map and found the location of Prague.

When my father gathered from my talk that I do know how to read a map and railway schedule, he allowed me to take a journey and gave me 50 guldens. During my travels I lived on rolls and slept in waiting rooms. Besides other deficiencies the ignorance of writing bothered me most. I did know how to write but I had to admit that nobody could read what I wrote. I was ashamed to give merchants copies of such contracts. There were many other things that I had to be ashamed of.

It was above all my handwriting and grammar, untidy clothing, ignorance of manners in better society and finally my age of sixteen. Sometimes the merchants would look me over and considered it an offense to their trade when such a smudgy - faced boy like me has ranked himself among the travelling salesmen. They often endeavored and succeeded in taking my courage away.

In other persons - and these were apparently the friends of youth entrepreneurship - my young age produced enthusiasm. They were enthusiastic about seeing a young Moravian coming to offer them a business contact. Altogether I spent fourteen days travelling, I brought home a large number of orders and from the 50 guldens brought back home full 35 guldens.

The discovery of Prague and the new way of selling were for our business the same as the discovery of America was for Spain.

Now it really started. Now it was possible to keep expanding our production beyond limits because the new way of marketing was not bound in space. My father saw himself approaching closer to his dreams and his dreams used to be daring even if his pockets were empty. I remember one incident which happened when we were still poor and which even today afford me the insight into the character and plans of my father.

It was at the fair in Hradiste. My father was standing in the circle of fellow shoemakers and said, pointing at the smoke-stack of Mayo's sugar works: "My boys shall one day have a smoke-stack just like that."

The fair was bad and nobody had any groschen in their pockets. Everybody was secretly wishing to hear: "Let's go and have something to warm up." But when it happened it turned out to be too much for their numbed bodies and sunken minds. This was actually a blasphemy to our collective misery.

Shoemakers drew closely around my father and started cursing him and ridiculing him. I was afraid for him and even angry with him and imprudent utterances. But my father did not give in and the growling shoemakers dispersed back to their stands.

In those days there were not yet as many smoke-stacks as there are today. In the region known to our marketmen there were only two: in Hradiste and in Napajedla. The one in Hradiste belonged to the Mayos, rich and lofty Jews, and the other one belonged to Count Baltazzi.1) It was unheard of that some ordinary person of the Czech (or as we used to say Moravian) origin would ever dared to aspire to something like that. That's why the shoemakers were so upset and could not forget and forgive my father for many fairs to come.

1) Aristide Baltazzi (1853-1914) was an excellent horseman and horse-breeder. He married Maria Theresa, Countess of Stockau, and through her he came into possession of the famous Napajedla stud, which he made known the world over.

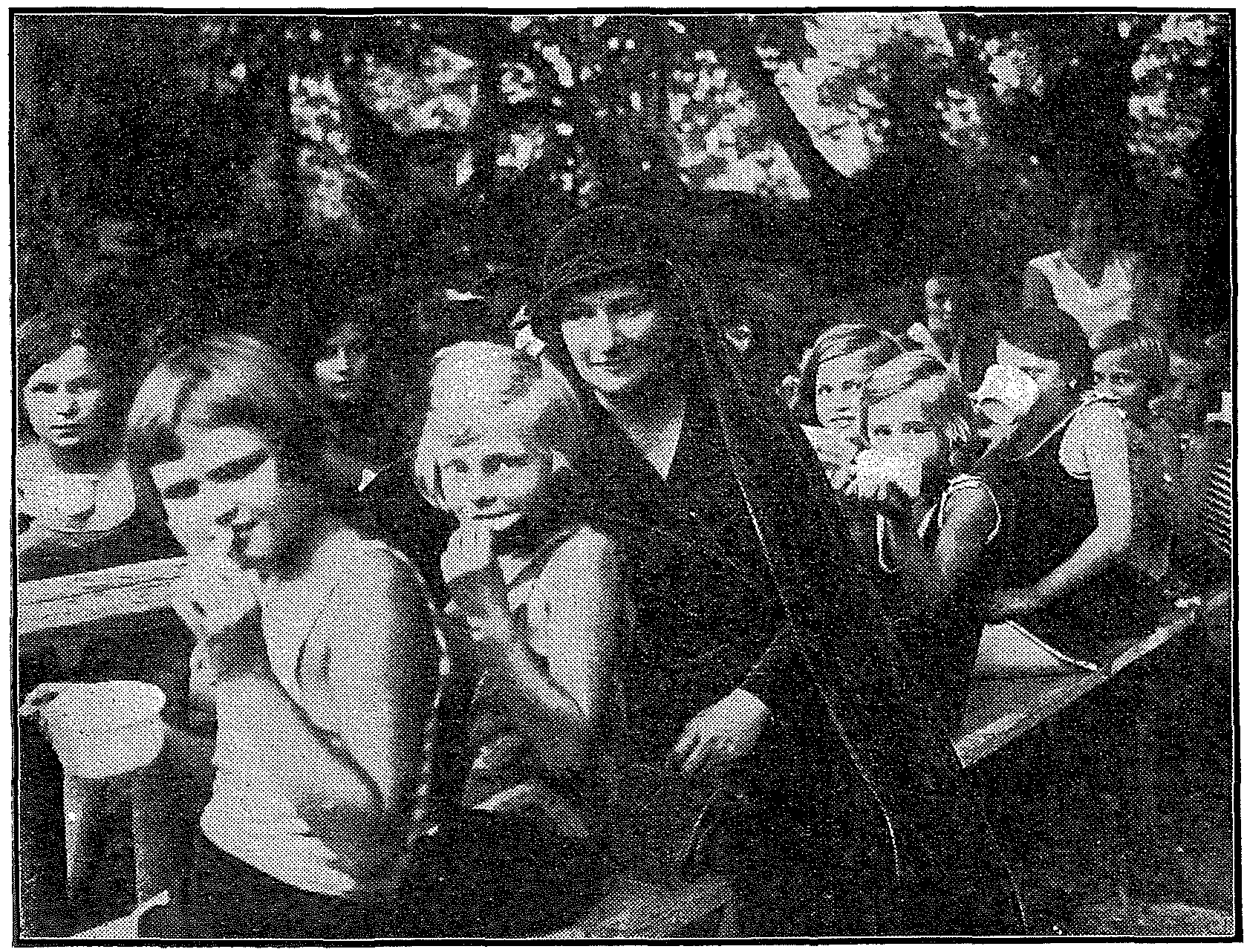

Anna, Tomas and Antonin Batas, the founders of Bata Enterprises

In the year 1894 we parted with my father's business forever: that is I, my brother and my sister Anna. Our father now paid out mother's dowry with interest and without hesitation. For all three of us it amounted to about 800 guldens.2)

2)A monetary unit, from Dutch guilder or golden (florin), in Czech "zlatka" or "zlaty", meaning "golden" or "piece of gold".

His generous act required courage. It is not easy to lose both able partners and a good deal of the capital, all at once. But our father never was short of pride, courage and the desire to do good for his children.

In 1894, my brother Antonin registered in his name a shoemaking business in Zlin. According to trade law I was registered as his journeyman. But there was a quiet understanding that all results will divided equally between the three of us.

Our independent entrepreneurship was motivated by our desire for better life. We started a modem business. We established precise working hours from 6 in the morning till 6 in the evening, with a one-hour lunch break at noon. We introduced wage payments on a weekly basis, for us and our journeymen; this was then considered infeasible for small businesses.

In those days it was customary that wages were paid to journeymen only as the sales money were taken in. There was no fixed and regular working day. One usually worked from daybreak until about 10 o'clock at night and on Saturdays or before fairs until the next morning. At the same time the "Blue Monday" was honored until the next work itself too seriously.

The young people between 18-20 years of age do not usually need much money in order to feel rich and we have enjoyed our riches to the fullest.

Although we did keep our promise not to smoke or drink, as we pledged to our father, we did use up our freedom by wasting our time. We have cultivated numerous contacts with "better" society and were ashamed for our work.

Equipment and material was bought on installments, via six-month bill of exchange which was usually extended when payable.

One year after we invented our "better life", our creditors started to grow increasing by weary of further extending our bills and thus perpetuating our business glory: they emphatically demanded their own. My brother was about to enter his military service and considered it inevitable that our business should fall apart and we should declare bankruptcy.

Our one-year independence thus ended with the loss of the entire invested capital of 800 guldens, besides that we also managed to squander about 8000 guldens of our creditor's money. It did sound impossible but it was true.

Until that time I have never burdened my brain by thinking about what is bankruptcy. Even subconsciously I was laughing at slogans like "The debts don't get wet" and such; suddenly I was staring the bankruptcy in the eyes and my hair started to bristle. I saw that bankruptcy is actually death and I wanted to live. My longing for physical existence was equally strong as my opposition to moral death. The penalty which I imposed on my body and life took the form of labor and self-denial to repay for the flightiness of the first year of our independence: it was my guarantee that never again would anything like that happen in my life.

There was no bankruptcy. Our creditors, when they saw my transformation, did not insist on immediate debt repayment and some of them have remained my friends until this very day. I managed to repay all our debts within two years, at no detriment to creditors whatsoever.

During the years 1922 and 1923, after the revaluation of the crown, there was time of general declarations of debt settlements in our republic. Some innocent establishments fell into the settlements, but of course some others took advantage of the seemly opportunity. Business ethics and mutual trust started to decline rather rapidly. Even the best did not appear to be good enough.

At that time I found it useful to explain my views on bankruptcy as follows:

Our enemies are broadcasting that we are bankrupt. My associates walk around me fearful for their jobs and incomes. Our customers look at their shoes and search their conscience whether it was not precisely that hundred they just saved on their price which caused the disaster invented by our competitors and spread around by unfriendly press. I must tell my workers and customers the truth because I do want them to believe me again next time. Our slanderers were incorrect when they wrote about my riches. I do not possess my wealth. I only have shoes for my customers. That's the same kind of possession as telescope represents for an astronomer or violin for a musician. Without it I could not give my workers work and my customers the shoes. I would then be about as useful to the world as a musician without his instrument.

That I am not a bankrupt you can realize very easily because you know that a bankrupt wants his creditors to forgive him and they would not forgive him if he would keep insisting that he was not bankrupt.

It is more difficult to convince you that I cannot ever be a bankrupt. These are the reasons: First, I come from the old world when people still believed that bankruptcy was dishonorable deed, especially so when a bankrupt ended up better off and his creditors worse off. Second, I already learned during my adolescence how to overcome bankruptcies.

When I was 18 I took part in founding today's establishment under the name of my elder brother and with participation of my sister with total capital 800 guldens. We considered ourself to be rich. We did not lack neither time nor money for our pleasures. But within a year we lack the money to pay our debts and for goods. Futile distrainments only disclosed no assets and the books showed numerous unpaid bills of exchange. At that time my brother started his three-year military service, when I recognized that a balance sheet deficit does not yet imply bankruptcy. In assessing the assets, businessman rarely takes into account his energy, diligence and business talent - yet, these are his greatest assets.

But I did not possess even these assets. I was brought up in bourgeois town and I used to look down on physical work as something undignified. I did not know of any other kind of work. Yet, I did not go bankrupt. The shame I felt for the bankruptcy of my brother's establishment, for which I shared the responsibility, taught me to work and save both time and money. With my own labor I overcame the bankruptcy and paid off my creditors in full. Thus I came to the conviction that bankruptcy is a question of morals. As to the rest, I am sure that many of you remember the story well.

There are also bankruptcies caused by misfortune, there are even bankrupts who do not wish to survive their shame. But neither these nor the light-minded, well fed and happy bankrupts represent any guarantee for the creditors. To creditor, the only guarantee is a businessman willing to pledge to his creditors not only all of his visible possessions, but willing to give himself in the form of work performed perhaps to the collapse.

On such human virtues stand large enterprises, big banks and empires. Germans call it "Geschäftstreue" (business trust) and Schiller wrote a great poem about it: "Die Burgschaft" (guarantee).

I do not wish to dissuade you from withdrawing your savings from the company savings bank. I just want to tell you that before you entrust your savings to the big palaces you should take a good look at how high are the moral values of people who work in them.

My neighbors, the shoemakers in Zlin, found themselves often in the similar situation as I did, the difference was that for many of them bankruptcy led to their physical death. In the worst predicament of all of us was actually my uncle Frantisek Bata. He was the first shoemaker I robbed of his independence. I visited him just before establishing our own independence. He lied in his bed, buried in the straw. All his clothing was stacked upon him and even though it was early in the afternoon his little chamber was in almost total darkness: his window was covered with something to prevent drafts. It was very cold.

I looked around for some fuel and food. But near the small and rusty iron stove was nothing suitable for fire.

Obviously he had not made any fire for a long time. On the bed there was a chunk of very hard bread, gnawed and nibbled over a on all sides. My uncle finally freed his head from the rags and tatters in order to see the visitor: he recognized me immediately. When I asked if he was sick, he insisted that he just caught a bit of cold. He was very much at a loss. He apologized about the looks of his home.

I told him that I would send something to eat, but he refused. He pointed to the piece of bread and said he still has four guldens "for the hides" and that he will be able to sell something again. He was proud and would rather die than ask for a bite to eat. But he was not a good craftsman, not even a mediocre one.

One could see that at fairs when he was among the others. On his pole he had at best four pairs of small shoes and he was happy when he sold two pairs and took in three guldens. My uncle was very slow but he was not lazy. Even this hibernation in bed served its purpose: it was February and there were no prospects for business.

There were of course many people like my uncle in the area: hiding in bed during the times of worse prospects, avoiding the expenditures for fuel, light, clothing and partly even for food. Those who did not put up the light through the entire winter, arguing that they did not earn enough for that, they were many.

My uncle was very hard-working and persevering but nobody in the area was looking for such rare virtues. There was not yet today's dead-end local railway in our area.

I taught him how to sew children's babouches. He made 20 pairs a week. Even such modest but permanent and regular income helped him back to health, even his threatening cough went away. Moss caulking disappeared from the window, the chamber air was fresh, there was a fire regularly flickering in the stove and a clean sheet appeared on a made-up bed.

When i finished the four-year local school and started the apprenticeship at my father's shop, it was clear to me that human society is divided into two kinds of people: gentlemen and non-gentlemen.

Such classifying into gentlemen and non-gentlemen is taking place already among the schoolchildren. Those who went on to high school were young masters and those who went into apprenticeship were condemned among non-gentlemen for all times to come.

The life of students had to resemble the life of future gentlemen and so it was quite natural that students went for their walks with professors right after four. This was recognized by their parents and even by their brothers who performed necessary manual tasks for them so that they could continue their walks. We apprentices, both in crafts and in business, we had to work long into the night.

I myself have decided to become an apprentice. But I also wanted to be a gentleman or at least to become one and gain my entry into better and cleaner rooms, among the "better" people. So I tried to mingle with the students and for that purpose I had to undergo such flights and troubles that it is impossible to count or describe them.

When I learned my gentleman's speech by reading books during my noon and evening breaks and procured my gentleman's clothes, I was ready to approach the small groups of the noble society of students. I soon noticed that citizen ropemaker's son - also apprentice - was watching me very attentively. He was the only apprentice who managed to stay with the students.

For many occasions I listened adoringly to their gentlemanly talks, looking for an opportunity to show that I too knew how to talk nicely and a form coherent sentences. There was this talk about whether to return home from an outing or whether to continue a bit further. Grasping unhesitantly such a rare moment, I remarked that it would be better to go home because a storm seems to be gathering its forces. The ropemaker, disguised as a student, reminded me that they knew better what to do than a cobbler's apprentice. That was a blow. It's hard to remember what happened after that. I know only that all of us turned silent and that in the later years I regretted not giving the ropemaker a good hiding, even though in those days roughness and combativeness of youth was yet recognized.

Although my father was glad to see me in the society of gentlemen, he did not tolerate my high-society whims during the working days. After finishing my apprenticeship at 18 I become convinced that I was ripe for independence. I moved both my elder brother and even still elder sister to form a company so that we could all become manufacturers and masters. My father realized dowry. He reminded us and especially me, that I was taking also experience and business knowledge acquired during my travels undertaken for his money. He did not want to profit from it, he just wanted to indicate that I should not underestimate the dowry which comes from him. He was right.

With choosing the place where to settle we did not have too many headaches. It was a matter of sentiments. We decided for Zlin because that's where we were born: we ignored its remoteness from a railroad or even from a larger trading town; it provided absolutely no conditions for our trade.

Our Business was registered in the name of my brother Antonin in Zlin. I was still under the age of 18. According to law I became my brother's journeyman. We rented two small rooms and soon filled them up with machines and material, all about, of course, without money: machines on installments, material for bills of exchange. Production was factory-like right from the beginning. It did not bother us at all that our factory had only two windows. We decided our working day from 6 in the morning till 7 in the evening, with one hour break at noon. In Hradiste we started at daybreak and labored until the bedtime, at about 10 p. m. We did not provide meals for our workers. Our payday was regularly on Saturdays, not as it was then customary in business to settle worker accounts in the spring and in the fall, but mainly during separation. That proved to be a reasonable measure: it was copied after the factory shops where I used to work sometimes as a worker, trying to learn about the usefulness of some machines on behalf of my father.

Things were more difficult with the work we set for ourselves. We did went to work also at 6 in the morning (also in winter), alternately each of us one day. But it did not help our work because we were ashamed of it. Now, as an independent, I could show off my knowledge of the better society and its demands. We actually went to work in our Sunday clothes, played an afternoon hour of billiards in the cafe and then went for a small glass of beer among the better people. During the day I argued with my brother about who should do the gentleman work and who the non-gentleman work. Consequently, neither kind of work was done, except the signing of bills of exchange which my brother, as a firm owner or chef, actually signed with great ceremony and ostentation.

So it went, from fall until next spring. In the spring, the only change in our occupation was that my brother stopped signing any new bills because there was no credit. Instead he started signing extensions of their maturity because there were no money to pay them off. At the end of the summer our creditors lost their customary respect of a supplier to his customer. They commenced to threaten us with law suits. The suits soon came, together with distrainments. I actually had to pledge all our goods, i. e. all our possessions, to the credit bank in Prerov. With the 800 guldens I paid off our worst creditors who were already pulling us down into poverty and humiliation.

Oh, those black capitalists souls, oh, the unjustice of this world. We worked at least as much as all the other masters and even more, because we started at 6 while the gentlemen arrived at 8 or even at 9; we certainly spent the least. In the pub we often ordered only the small beer: they actually laughed at us and the innkeeper became suspicious. We did not smoke. Still, we were just about to be expelled from the society of gentlemen, we were supposed to stop being industrialists.

At that time my brother was entering his three-year military service. When we realized that there were still about 8000 guldens worth of our bills in circulation, several thousand guldens of non-convertible debts, and assets of only about 1000 guldens, my brother told me to declare bankruptcy and left. When we failed to pay additional bills the gates of hell have arched over me. All, people and creditors especially started to carry out justice. They told me quite openly what they thought of us for a long time, when we were still gentlemen. It became obvious that they were very concerned about whether I understand them fully. Into their educational work they put even more effort than the teachers who priests who used to teach me morals at school, and more energy than the teachers who taught me long division or how to find Silesia on a map. Ever so slowly I started to see that these black capitalistic souls were right and that the life of a gentleman was unfit for a man who did not somehow secure safe access to the state or local treasury.

I stopped going to the society of gentlemen, that is to restaurants and cafes, and thus I gained some time to think more about life. I started to calculate how much I could earn if I devoted every moment to work, including even the despised worker's labor - the ungentlemanly one.

As a piece of ice does not melt at once, even if thrown into the greatest heat, so my desire to resemble gentlemen was not overcome all at once. Therefore, at first, I placed my cobbler's stool so that nobody could see me working but I could see easily all comers. Nobody was supposed to see how low I sank. But that was for a short while only. Very soon the work conquered my entire person. All blessings of all my life have started on that day. I came to understand the foolishness of mimicking the lazy people, masters or non-masters alike. In work I started to discover more and more grace and inner satisfaction.

Through performing all worker's jobs I discovered new roads to material savings and worker task simplification. Now I did not mind the lack of money or credit. I was selling my finished goods in Vienna to those who paid cash on delivery - of course, for the prices dictated by them. I showed the order to the supplier of raw materials and asked for a week-long credit against the bill. They laughed, but they did try me with small amounts. I carried the hides on my back from the midnight train at the Otrokovice station to Zlin (10 kilometres). During the night, one worker and I have cut the hides up and issued them to workers in the morning. Workers then worked days and nights until completing the whole task. Then the workers slept and I journeyed through the night to deliver the goods and bring new material and money for the wages.

Sometimes I gave the creditors or paid for the hides more money and there was not enough left workers. In such cases they got only retainers for bread. But even of the bread they often needed more than they had money for. Those who had some credit often voluntarily gave up their retainers for the sake of their even poorer colleagues. But even when the pile on the table shrank to mere sixers, which I wanted to salvage for my own household and for my sister, somebody even hungrier showed up I could not resist those begging eyes rivetted to the remaining sixers. My sister did cry some, that there was no bread in the house for more than a week, and no credit too, because we forgot to pay the baker several times. So I worked, in the midst of volleys from dissatisfied creditors and dispite my considerable and frequent payments.

Jewish creditors were much calmer. They were probably quite well informed by their co-believers from Zlin. They knew already that one cannot achieve anything through execution; they obviously also learned that I pay my debts with something nobody could distrain - that I pay my debts with my blood.

During the Christmas holidays we needed more money for our workers. I travelled all over Austria in order to collect money for the delivered goods from our smaller customers. It was wet and I went almost barefoot. I wrote to my sister that I would like to have leather shoes made for Christmas. We did not yet make leather shoes at that time. When I was approaching Zlin, actually running because my shoes had no soles and it was bitterly cold, I was passing people going to the morning service.

I did not sleep for the whole week, except perhaps somewhere on a bench in a III-class train. So I woke up quite late and my sister was already at church service. Beside the bed I found my new shoes. I joyfully put them on, ready to go to the tavern, among the gentlemen again, for the first time after a very long period. But alas! As soon as I took my cue-stick to play some billiards, there was this shoemaker from the other, non-gentleman room and he started rather obviously looking my shoes over. "And who is going to pay for them shoes here, you gentleman-beggar?" shouted the cobbler, pointing to my shoes and looking around the gathered society of gentlemen.

Such a trashing could not remain without its good effects. Never again did I ever put on a piece of wear without first convincing myself that it was already paid in full.

It was also apparent that people were quite sure that my education was not yet complete and that it required their continued effort and care.

At the year's end I took my inventory. I wrote up carefully and even over carefully all my possessions and debts. A teacher from an industrial institute kindly and clearly arranged the inventory according to the book-keeping rules. The inventory was not absolutely necessary because I carried every little cutting, every little debt and the overall state all in my head. Nevertheless, it was useful and beneficial because all those various and scattered numbers finally received their totals.

It turned out that my assets were now almost equal my liabilities. It was no surprise to me, but it was a big surprise for those who needed a proof of my little miracle. But it was neither miracle nor a good luck. It was the result of my new ability to utilize time properly. Better utilization of time allowed quicker turnover, quick turnover facilitated cash payments and ready cash brought cheaper buying.

I was ahead of my learned and educated competitors in all areas. I bought my own material, I cut it and I clipped it, I distributed it among the workers, I myself inspected and accepted each and every pair, I paid my workers and I did all the booking and accounting: all with the greatest speed and at considerable savings of time, material and money. My skills reached such proficiency that during a single Saturday I was able to take care of 100 workers for the whole week: evaluate quality of their work, count their product pair by pair, issue new work for the coming week, record the accepted and issued work for each worker separately, into their own work-books, calculate and pay their wages and account and record all the customer-supplier affairs normally related to production or sales. As a result, I was able to devote the entire week, except Saturday, to work.

The books showed that my assets were still a little less than nothing, but I already felt like rich and independent entrepreneur. I knew that it was only a matter of a short while before all my creditor troubles stop and I would have the right to stand up to anybody.

In the middle of 1896 I stood close to that long-yearned-for goal. One day there was a message about the bankruptcy of Koditsch & Co. in Vienna. On the first day, I did not pay much attention, but felt rather sorry for my father, knowing how carelessly he signed bills to that firm, as we, i. e., my brother, also did only a year ago.

My affairs with Koditsch were all in order and when my brother told me once that the company was asking us to sign some bills, with the assurances that, as always, they would pay them out to themselves, I forbade him to sign anything. Besides, my brother knew that we do not buy from that firm any more.

The next day I received a despairing letter from my brother: in spite of my explicit orders, he was not able to resist the urgings of one of the firm's partners, who recited to him all the kind deeds his firm extended to our father and to us; besides, he assured him, Mr. Tomas, that is I, will never have to know about the signed bills. He signed for about 20 000 guldens of such bills. In fear I turned towards the door, to assure myself that executors are not yet entering. I dashed to the corridor, grabbed my bicycle and started towards Uherske Hradiste.

Startled looks of passers by reminded me that I was riding without any head-cover. Because in those days such thing was considered a sign of definite madness, I returned back for my hat.

In Uherske Hradiste I spoke with dr. Konecny who appreciated my entire tragedy with his whole heart. Without supper and without light we sat, talking late into the night. I left for Vienna the same night having reached full understanding that I had to pay.

The fact that I received no countervalue did not matter at all. It might have been relevant in dealing with Koditsch Co. directly, but it was of no use against those who the Koditsch's bills actually purchased. These must be paid first and then the money sought directly from the bankrupt Koditsch. There was of course a service as invalid, on the paragraph which declared all bills signed by a soldier in active service as invalid; on the other hand, the business was under brother's name.

In Vienna I promised to pay brother's obligations to all creditors of Koditsch Co. The amounts involved were many times higher than my earned, small and still young capital.

I worked my way out of this crisis relatively soon. Although the deficit between assets and liabilities was larger than in the first crisis, larger moral values were also present. My trust in work and the trust of suppliers customers and employees in me.

Yet, this crisis did bring about moral harm to our family: it caused the bankruptcy of my father. I was not able to save him. Only in later years I was able to pay creditors damages caused by father's bankruptcy, to the extent I was able to find them and validate their claims.

One day I realized that I would not be able to fulfill a delivery contract, namely the contract we had with a well known firm H. H. in Vienna. With this company we closed contract on delivering summer canvas shoes with leather soles which until then were not being produced in our lands.

I overestimated my educational abilities. I thought that I would be able to teach the hand production of tack and "turned over" shoes much larger number of workers than I actually managed within such short time period.

My name was again in danger, this time in connection with the reliability and fulfillment of our delivery agreements. Only something extraordinary could help here. Machines? Between me and machines was a large gaping abyss. I used to read Tolstoy's books proclaiming return to simple and primitive life and I became one of his worshippers. In my ears also ringed the words of my business neighbors who talked about machines in the same way as Austrian general staff discussed enemy armies.

I did not have time for philosophizing. The issue was timely fulfillment of accepted obligations and any help was to be considered, wherever it came from.

Cutting of bottom parts was difficult work and I resolved to buy a book-binding press and try to use it for punching out the sections. It did not work. It was necessary to redesign it as a whole.

This was a huge undertaking. Because of meager technical experience, inadequate knowledge and isolation of our lands, it required more energy than building our new power station.

But the success was considerable and my animosity towards machines was seriously rent. The biggest problem was production of bottoms and it still remained unresolved. I journeyed to Prague to see Mr. Vrana, shoemaker in Vinohrady and publisher of "Obuvnicke listy", asking for his advice on shoemaking, but now they were looking for manual shoemakers again and the use of machines was on the decline.

I came to Prague in light, canvas shoes and luster clothes, without a bag. Disregarding the discouraging reply of Mr. Vrana, I left directly for Frankfurt a. M. Some company wrote us from Frankfurt about their shoemaking machines. I left their address at home, but the policeman in Frankfurt obviously knew about the shoemaking machinery more than all of us together and he sent me to Moenus A. G. I was hardly able to gather sufficient courage and enter the representative palaces of the rich companies of Frankfurt, in my poor clothes and with even poorer knowledge of German language.

I was amazed. I was looking only for punching and sewing machines about which I did hear, and suddenly I became transported in the midst of an empire of incredible variety of machines. I saw machines designed for performing all shoe-making tasks, no matter how small. But alas! All these machines were steam-driven only and I did not have a steam engine nor could I dare to even think about acquiring one. Also the prices of these machines were well beyond my means.

I therefore bought only some hand tools: ingeniously constructed pliers, cutters and magnetic hammer. My head was on fire during the entire trip back home.

I was not worried about fulfilling my obligations anymore. They suddenly became quite petty alongside these giants of steel, capable of performing a hundred times, or even thousand times more than all my obligations altogether. I was fully satisfied with discovering the sources of enormous power, even though unavailable to me at that time.

My head was burning from confronting my views on human society, the view of life derived from the vantage point of my twenty years and from the books of Tolstoy, poems of Svatopluk Cech (his "The Blacksmith of Lesetin" and "Songs of the Slave" I knew by heart) and all our literature about Czech Brethren; the view learned also from listening to people around me.

I was a collectivist and even something like a communist, but a socialist I was for sure.

The contemporary capitalist society I considered to be good only for bad people, like vampires and idlers. I dreamt about the simple life of Tolstoy. As soon as I pay off my (i. e., my brother's) debts and manage to earn a bit more, then I'd buy a small farm and I'd sow only enough to maintain myself and my family.

Cities exist only to enslave farmers and factories exist only to enslave workers; merchants exist to live as parasites from the work of others.

If I should need a spade or tools, they would be produced in a socialist factory, as described by Zola in his "Work".

But from the window of my train, I saw the Rhineland and its factories - and some of them were making shoes.

One could see nice human dwellings and strong, healthy and well-clothed people. The steamers on the Rhine were tugging multitude of large ships and I was busy calculating how large were the inventories of human necessities stored within them - and all that for all those people here. I guessed already where all this wealth and affluence came from. There, from those giants of steel, who on human command can produce anything necessary for human life. There, on the Rhine, the ships were taking to the sea the surplus products of those people, to be traded overseas for goods which they still lack; and these are stored in those ships over there, coming slowly down the Rhine in long lines. And in my feverish head there was being erected the smokestack prophesized by my father and I stood in the midst of these giants of steel, ordering them to work, calling: "Work, work!"

Right away there was the socialist in me. He chased away the image of factory owner and called me names of vampires and slavers. No! I will not become the hated capitalist! I will not, I kept reassuring myself, as soon as I have earned a little to buy a small farm.

The socialist was driven out of me by my uncle Bata, Vlcek and many workers whom I often visited and saw how that regular even if small income did improve their lives.

These people often looked at me with fearful eyes, whenever they heard some doubts about Bata's ability to survive: as if their lives and not mine were at risk.

Is it permissible to abandon such people? What are they going to do in the meantime, before that collectivism or some socialist order comes?

At home I found numerous prospects of Keats A. S. I correctly sensed that in that vast empire of enormous machine might there will be some appropriate dwarf who will save me. I found him in the Keats catalog. It was a punching apparatus which increased workers productivity many times over and assured the fulfillment of orders on time.

I myself had learned to control the steel dwarfs perfectly and I also taught the others. I supplied them with appropriate work organization and with the help of additional minor technical improvements I expanded the production which by its quality and cost surpassed even the large factories organized to produce the same with larger capital.

Our books soon showed rapidly growing side of assets and equally rapidly declining side of liabilities. My wealth soon exceeded the amount necessary for buying that small farm and certainly more than I needed for myself, or even for my brother and my sister.

As long as I was on the defensive against foreign capital, as long as I fought to defend the honor of myself, my brother and my sister, as long as I worked to provide for the necessities of life - until then all my work was justified by the moral values derived from and maintained by my immediate surroundings.

Now I lost that firm grounding under my feet. It did not bother me during my work. After all, I did only what was desirable and necessary to other people. I provided them with the work they were seeking and which they urgently asked me, I sold only to those who wanted to buy and who expressed satisfaction with my products.

It was quite different however, when I took and hour off and went among the better people for a small talk. Or if I opened a newspaper or picked up a book. From all sides and from all comers I was shouted at: "You leech, you slaver..." There was not yet my name associated with all this, but attacked there was the ideal which was starting to take shape in my mental shop: the ideal which was supposed to become a new moral foundation of my work and which now had to struggle hard for its existence with its older brother-socialist.

My friends were apologizing for me, insisting that I do not belong in that evil society because my production is very small; to me it was like they were simply saying that I am only lesser than the others.

I did not wish to be a villain. I thought and read about cooperative enterprise but I recall the experience with my brother, when each and every work was talked over, but none was done.

I saw everywhere the bad result of cooperatives, even of those consisting in which my brother did recognize this right.

And how would the things go in some such corporation where all profits would have to be distributed among co-workers?

How would we then buy that steam engine needed to utilize the help of those German and American giants of steel? There was no way out. I had to stay in my place and become that hated and loathed industrialist, leech and slaver, in order to serve the people.

After such decisive victory, the steam engine of 8 HP soon came, together with the steel helpers, the first real factory building also came, together with my father's foreseen smokestack, even though only metal-plate one.

In 1904 there were already three smokestacks smoking. We were buying small, older steam engines which did not work well and there was always the need to obtain new, better power sources and new, larger factory building, together with additional specialized machinery.

I did not trust my knowledge, acquired through work and travels in Europe, to start so many new ventures with confidence.

In that same year I left for America, accompanied by three young workers.

There I found many beautiful things, but most of all I liked the people. They did not wallow in prejudices about honor or dishonor of work. Such questions were resolved by their grandfathers long time ago.

Selling newspapers in the streets was good enough and acceptable for the son of high official, son of millionaire or son of worker. There were no students-gentle-men.

You could only see rolled up sleeves and joyful work. A six year old boy appeared big enough to his father as to be allowed to create his own possessions and to make his own decisions about it. Son was being led towards independence. He was not to feel his father's dominance. He was to become an equal citizen.

I am businessman - you are businessman, our skills are recognized by how much each of us earns. Father's eyes brighten when hearing about his son's new dollar, son is proud of his father and each of his new successes. Such attitudes are then transported from the family to the public. Mr. Miles showed me the factory of his competitor and said: "Can you imagine how capable that man must be if he can earn enough to pay one million dollars of income tax?" Interesting was that this Mr. Miles himself earned less than nothing, having increasingly more debts than assets. Nevertheless, he was very proud of his more skillful competitor. The soul of American man was not shackled by doubts whether or not an individual can amass wealth.

Such doubts were very much alive in the subconsciousness of our own society, thanks to old Slavonic law which was replaced only by force by Roman law. According to the Slavonic law, all community members brought and collected the fruits of their work in one barn. The products were then distributed among community members by the chief, according to his conscience and best judgment of need, not according to individual labor and merit. This was the old family socialism. Subconscious reverence for Slavonic law has been kept alive in the Russian literature, especially by Tolstoy. This also provided very fertile soil for the new socialism of Marx, which is essentially the same idea, but extended to the whole of society.

Concerning machines and work organization I did not find much new in America. This was to be expected with respect to machines, because for long time I maintained active correspondence with local machine factories. In the organization of machinery only the layout was of interest. I was changing my layouts several times a year and finally invented the pattern which even in America they considered to be best.

But the skills of workers were great. On some machines they were achieving ten times higher performance than our own workers.

Therefore i worked there as a factory worker, knowing fully that it is futile to tell people how to work and not being able to show them. I also wanted to experience with my own body the difficulties in attaining such high performances. From home I brought a high regard for my own skills. I was convinced that I can work skillfully on all shoemaking machines, but in America this self-confidence brought much harm upon me.

When asked what work I can do, I answered proudly that all and every work. The factory receiver only smiled and said "not needed", an answer I could not understand and explain for a long time. Finally I managed to advance so far as to be put on the line of job applicants and tested in one kind of work. I finally understood the legitimacy of receiver's contemptuous smile: I realized that in my lifetime I could not master all work to such perfection of performance as it was then normally required in America.

For some time I worked under the patronage of my landlord Berka in one bad factory in Lynn. I wanted to stand up on my own feet. The work was hard to find. Those who had work used to wake up before 7 in the morning, those who did not have work have to wake up before 5 in order to stand before the gates of some remote factory well before the work started.

So, I felt fortunate to see myself with rolled up sleeves - this coat of arms of America nobility - taking a test at one or the other machine. The foreman followed all my movements very intensely. I did not even have to look at his face in order to read my fate in it.

I was told by the laughter of other applicants, waiting behind me with equally rolled up sleeves, waiting for me to fail. They did not have to wait long.

Such tests I sometimes underwent about twenty a day and six times as many in a week. My mind became depressed and dispirited. I was fully absorbed in thoughts and feelings of a worker. I did not care about the dollars imported from America. I wanted American dollars. I wanted to measure myself directly with American man.

Once, on one such journey, I said to myself that I would not eat until I get a job.

And I got it.

From a rover and useless man all of a sudden I became a nobleman. My hands were tom and bruised, but my head was sitting firmly in its place.

With these personal notes ends Tomas Bata's own narrative about the beginnings of his work The task will be finished, but the notes remained but a torso. In the second part we shall continue by coherent and orderly publication of speeches with the help of which Bata guided and build his work.

Everybody who delves deeper into the life of Tomas Bata will find that this man, both a human being and an entrepreneur, grew stronger only by overcoming crises. In dealing with his business crisis we see how nineteen year old Bata overcame his personal crisis at the same time. There is a change in views and change in character. What are the characteristics of this change? Bata realized that business is not easy that it is not private affair and that the question of business survival derives from the service to others. He was not yet able to do always more than words: deeds. At that time he started producing and selling his "batas"; very cheap, light canvas shoes, so cheap that "anybody could wear them".

There are no direct records about Tomas Bata's view of his period of his business education. How did he deal with mental struggles in which, as the notes found after his death indicate, was entangled the spirit of a young, unusually talented and passionately feeling man? What were the struggles which transformed the worshipper and reader of Russian philosopher of passive simplicity into a man of iron will? What urges caused young Tomas Bata to abandon his dreams about simple, isolated life of a farmer and to plunge with all his heart into the industrial work, broad and noisy markets of the whole world? We do not know. All his document speeches, which are being published on the following pages, show already mature, well balanced man who knows his road and his goal, man who does not quiver even in the mightiest of storms and confusions of nations, in which all civilized mankind has been tossed about during the past twenty years.

When was Bata's idea of self-management born and why? Only one of his occasional speeches gives a distant answer to this most significant question. In it he says: "In America I liked the better and more equal relationship between worker and employer: I am master, you are master, I am businessman, you are businessman. I wished that such way of life would also pervade us here in Zlin. I wished that we would all become equal, somehow”.

In the world of business and industry one cannot survive simply with wants and wishes. Especially when in 1908 his brother died and the direction of business remained in the sole hands of Tomas Bata. Every single day one can demonstrate that people want income, banks want interest and customers want shoes: the ideals which are not manifested in money and success are of interest to no one. It is therefore necessary to give people work, money and shoes first, and more of it than anybody else could

In the meantime, the war came. Legends are being told about Bata's wealth acquired during the war. Never was this diligent, honest and extremely deliberate businessman closer to his fall as right after the war and as in consequence of the war. The two factory buildings of Bata Enterprises were in 1914 placed under military supervision and must bear the break in leadership authority where the last word belongs to military organs. From the war they emerge with four factory buildings, full of machines which are mostly unsuitable for the new civilian production. There is of course also a huge liability and a small asset. Liability is the enormous debt of the old broken state which did not pay for its goods and the concurrent duty to pay heavy taxes and property rates to the new state. The only asset were the people - the same people whose transfer from the army to production saved their lives and whose health was preserved and maintained through the factory provisions. These are the assets with which Tomas Bata started again: fighting the economic crisis, poverty and opposition from the left and right, he put through the implementation of his youthful dream about self-management of work. His was the giant effort, aimed towards establishing the economic engine of human society on firm and reliable tracks and securing it with energy and fuel, so that it could run and serve.

Let us note how is this period of struggles and searching reflected in Bata's public speeches.

The industry of our town was until the World War producing canvas shoes and sandals. That is, light domestic footwear.

Immediately after the mobilization against Serbia it has become clear to all, both customers and industrialists, that there is no need for that type of industry any longer. All factories stopped in that same hour when I brought the news of war from the district headquarters in Uherske Hradiste.

I just happened to be present there when dr. Janustik, our current county executive, received the mobilization order.

In a few minutes I was, by automobile, back in Zlin.

The mobilization order was very strict. All recruits had to reach their regiments within 24 hours.

The next day I drove to Otrokovice to meet the passenger train. I wanted to change to the express train in Hulin and proceed to Vienna for the purpose of obtaining work contract from the military. I missed the train and so I started after it.

The driver was Hubacek. He was an able boy, with good and trustworthy horses, and knew how to keep them in good order. We decided to sacrifice the horses. During the entire journey we kept standing up in the carriage, reins in one hand and the whip in the other. I with my watch in hand, my eyes following the jerking of seconds and the passing of milestones alongside the road. The problem was not to allow horses to fall too far before reaching our goal - and Hubacek understood this very well. The smoke from the express we spotted just at the sugar plant in Hulin. There was no hope. But the horses, as if understanding that having received their life from man they are also obliged to give their lives for man if needed; they performed the impossible. We still did not reach the station. I jumped out, crossed the railway pavement, through some freight trains, on of which was slowly moving, I entered the express from the other side. In Vienna I arranged nothing and got nothing. They told me the same story as they told to so many other applicants.

They are, they said, two old consortia (corporations), one for the land-defense army and the other for the army of the ministry of war. Both of them have 15-year contracts for supplying boots and shoes. The return journey was very sad. People at home were waiting whether they will be asked to go to work or to war. Frightened by those modern, cruel and death-dealing weapons, they saw certain death in joining the army. From that day on I went to Vienna almost all the time, either on my racehorse Elka or by train.

There was no time to spare. Our strict sergeant Kvapil did not allow any postponements and I received the news in Vienna that he was taking in the workers in handcuffs when they were late with their conscriptions. People were waiting at the station for a telegram from me.

By the third day I pocketed an order for 50 000 "siegl" military shoes, but at price which were of little interest to me.

It was at noon, several minutes before the departure of the express train from Vienna. There were no available cabs in the vicinity of land-defense ministry. In long jumps I ran towards the Ring. My legs used to be in a good order then. There were plenty of carriages there, but they were all occupied by officers arriving from the station and joining their regiments: I would not dare to take them up, not yet. I jumped into an empty cab going in the opposite direction. After a short fight with the cabdriver we managed to agree that he would take me to the North station. The amount I paid him was enough to buy a new horse. We caught the train.

The very same day I called on our mayor Stepanek at the city hall. I told him that I wish to distribute my order among all local factories and that I propose to establish suppliers' consortium in Zlin.

This first order was issued in the name of T. & A. Bata Zlin and was distributed among T. & A. Bata, Frantisek Stepanek, Kuchar brothers, Antonin Cervenka and Ludvik Zapletal, according to the number of punching machines. There was a great enthusiasm for it among the citizen of Zlin. I did not deserve all the thanks I received from them. It was not really so difficult to obtain the order because during my stay in Vienna the World War just broke out. It only looked difficult, especially to those who stayed at home and lost their courage for a while.

All owners of participating factories were young and healthy men, mostly soldiers, and they employed large number of workers, also mostly eligible for military conscription. It was by chance that I was the only non-soldiers among them. Fortunately, all these factory owners survived the war in good health and without harm. It was again by chance only that I was the one to suffer a serious injury. This was not caused by war. It was brought about by my haste which, as it was later demonstrated, turned out to be much less important than I thought at the time.

My arrival from Vienna was welcomed by people waiting at the local station and their joy seemed to be without bounds when stepping off the train I told them that I brought work.

During the war the plant was under military supervision. Our production reached its peak in 1917: 10 000 pairs of shoes produced daily by 5 000 employees. Of course, the critical shortage of leather forced us also into the production of wooden clogs, about 5 000 daily.

During the war we employed in our large numbers of men and soldiers from the whole county and their families were provided for from our company co-op. No matter what highs were the food prices reaching in the whole Austria, our company was selling both meals and groceries to about 35 000 people at prices only marginally higher than at the peacetime, and it paid the difference from its own means. This particular circumstance assured that the political collapse of Austria and consequent political upheavals and wild ideas by passed our firm in relative calm.

The firm, together with a number of other shoemaking factories working on contracts, was much more seriously affected by the economic upheavals. The long duration of the war and the changes in production required investments in machines which were mostly unsuitable for the civilian production and had to be redesigned.

Market situation was in the sign of total exhaustion. Raw materials were scarce and their prices terrible. People-customer went barefoot, but with money.

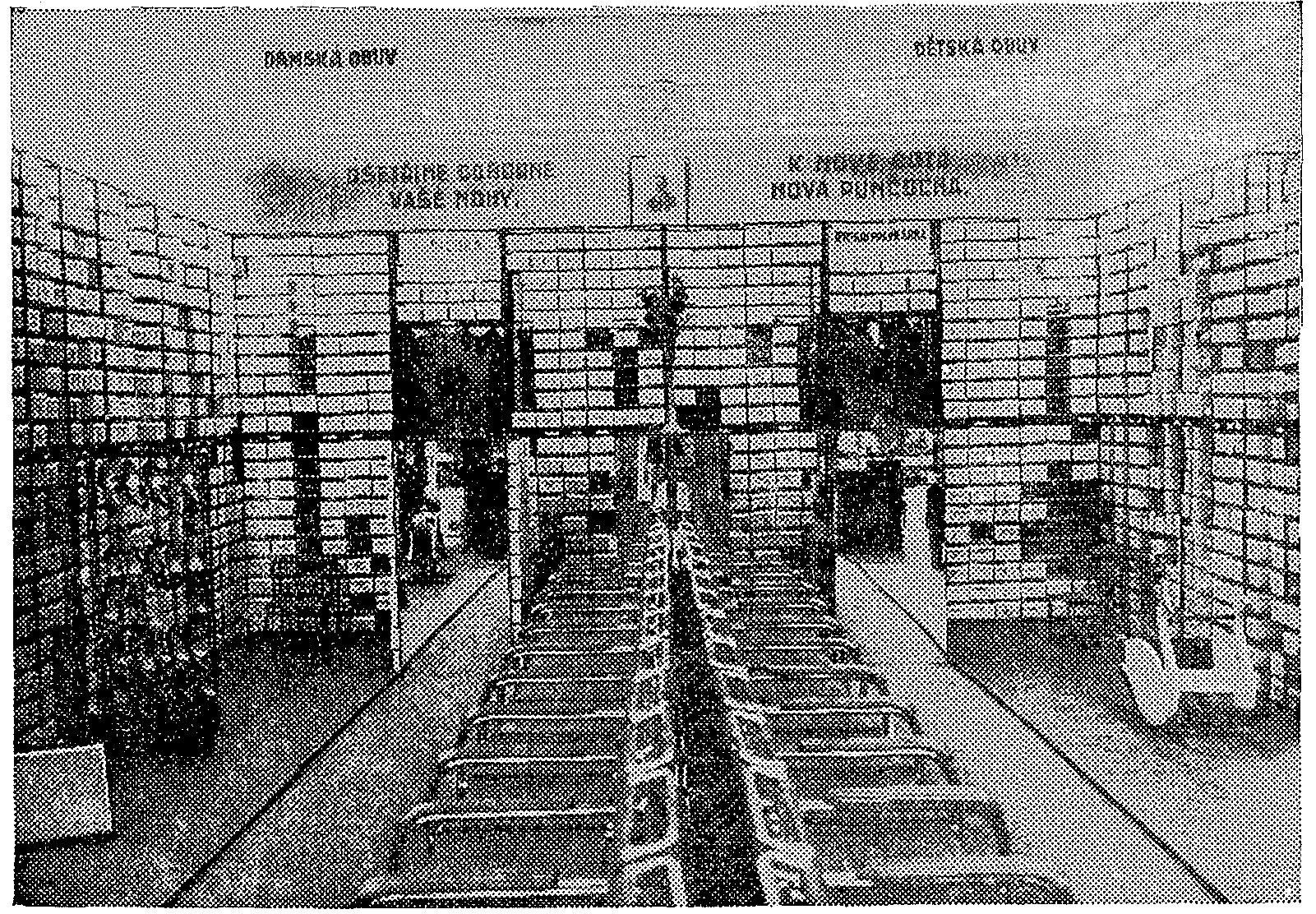

Bata, after changing the production, was set to continue in its pre-war price policy, but there was very little understanding from most businessmen. They did not want lower the prices when the demand was unlimited and supply truly precious. Bata therefore started to build its own retail outlets, introduced unified and firm prices of goods and slowly consolidated the enterprise for the new work.

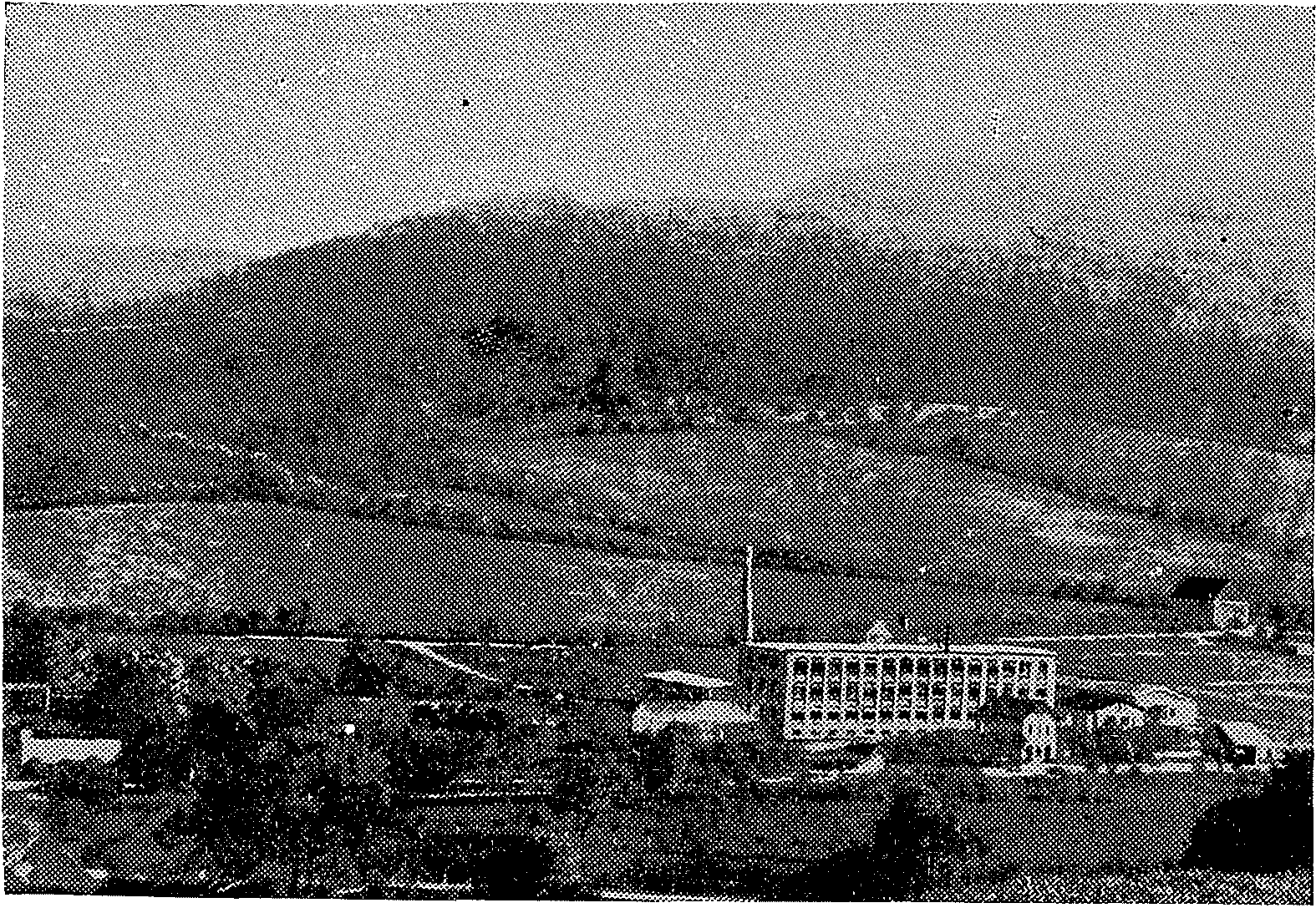

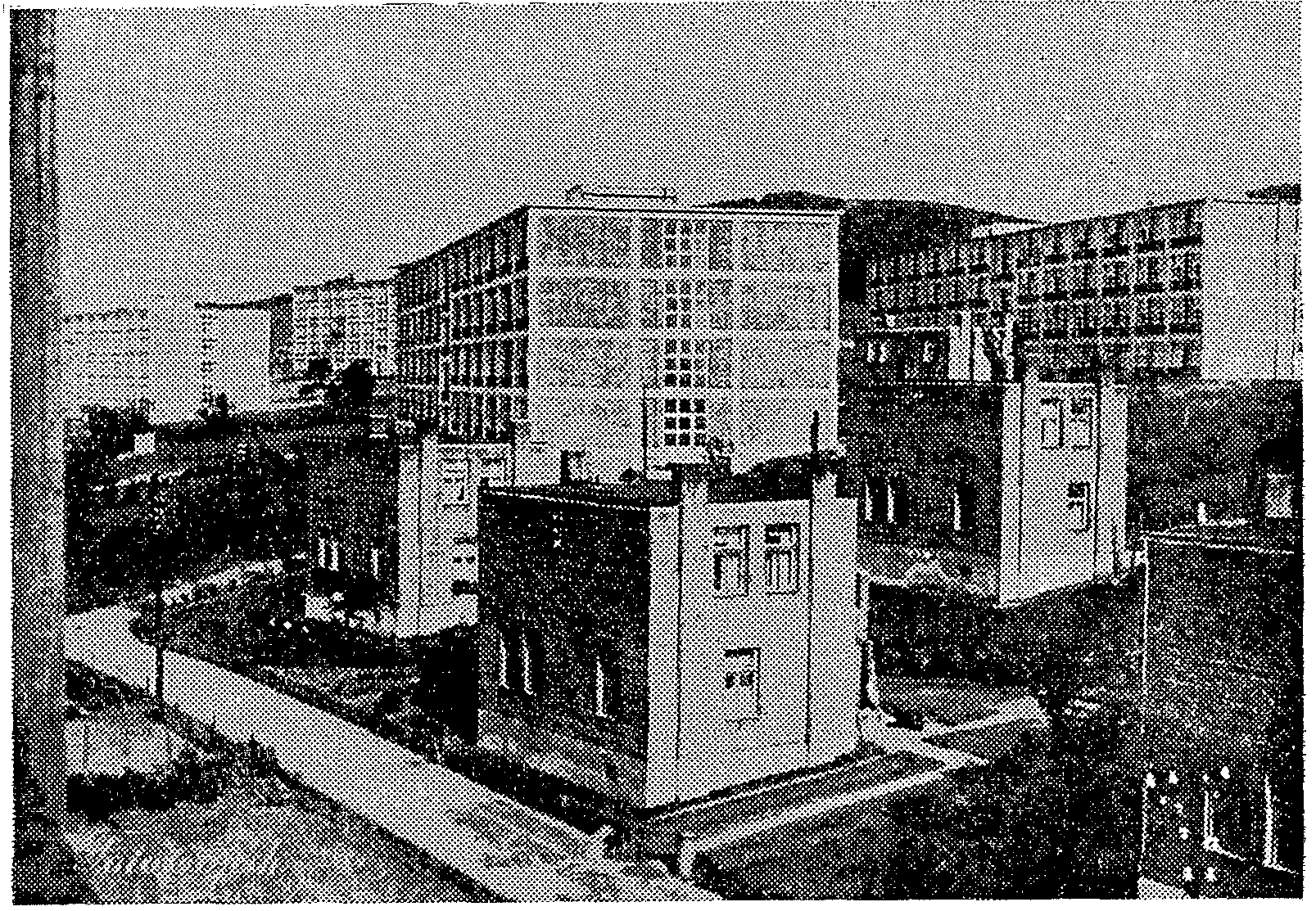

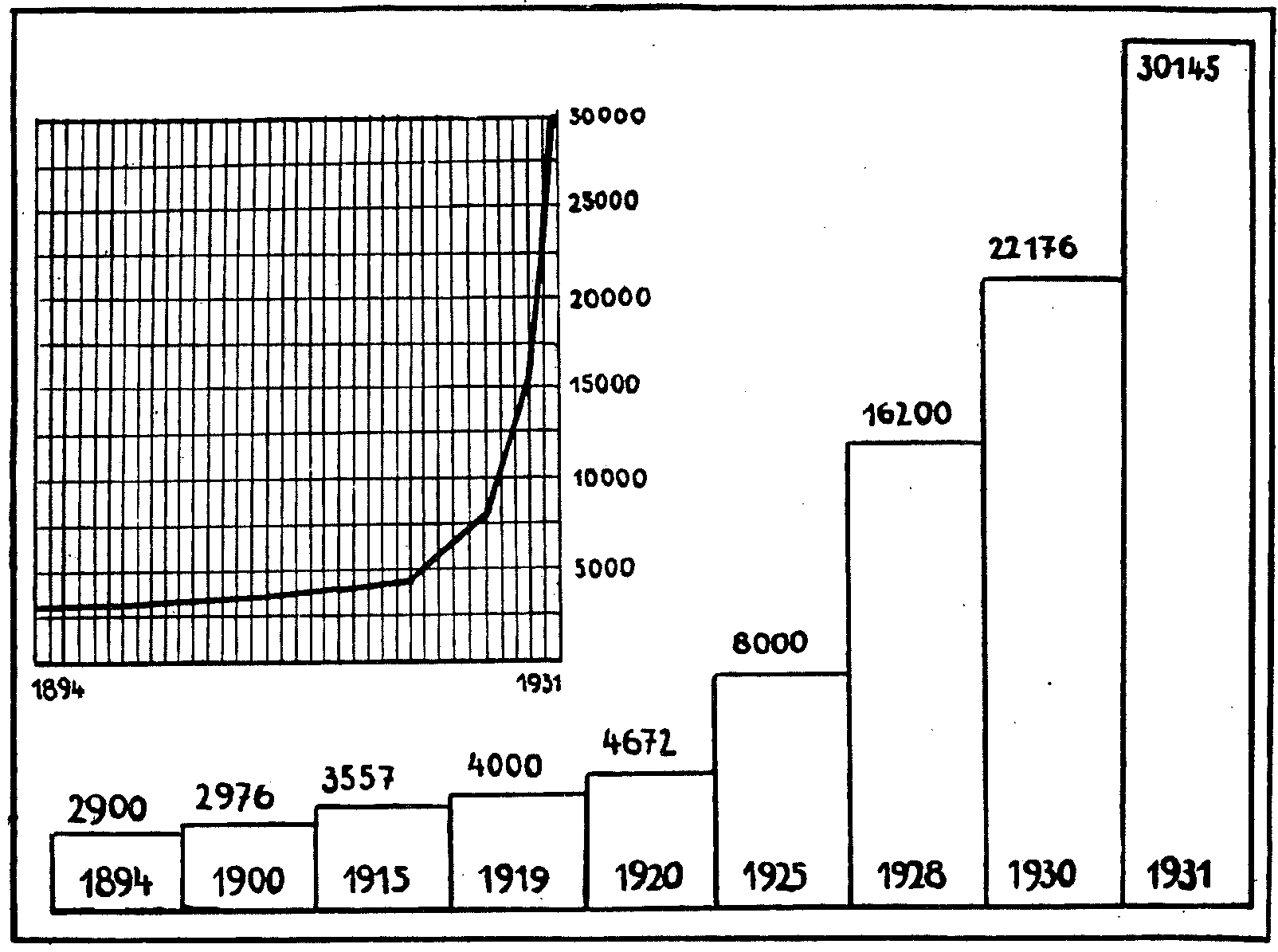

During the years when on all sides and all businesses the political influences were felt, Bata succeeded in convincing its employees about the harmfulness of such influences and earned their trust. In 1922, during the great industrial and monetary crisis, when hundreds of firms were declaring bankruptcies and additional hundreds were stopping their work, Bata carried out radical act which gained him sincere sympathies of the public. He reduced the prices of all his products in one day by 50 %. Judicious and careful businessmen considered it foolish and waited for Bata to collapse. Bata survived. At a fast pace he sold out his inventories, changing thus frozen capital into a liquid one while maintaining the level of production. He reduced overhead and curtailed losses. And from the year 1923 we can trace the steady and large growth of the enterprise, which grew from the 4 factory buildings at the time to some 50 factory objects in Zlin and 20 in Otrokovice as of today.

During these years of 1918 - 1923 the long years of apprenticeship of Tomas Bata had peaked and ended. During these years he attained highest and yet fully balanced expenditure of his energies. He knows what he wants and he wants a lot; he also knows how to get it. During the time of unprecedented destruction of material and moral values, in times of excessive vacillation and nihilistic mistrust, Bata comes to see his own salvation and the salvation of mankind in work. He sees that the old habits, relationships and unity of people were ripped apart and he feels that on these old foundations one cannot build any longer, one has to start again, from the beginning. But how? Bata did not find his solution all at once. All his speeches between 1918 and 1923 show that in addition to straggling for the survival of business, he also fought for the final resolution of the larger problem. He comes to it only in his speech on profit sharing and in expressing his views in booklet "Wealth for All".

This becomes clear from the introductory article of the first issue of the first volume of the company journal "Sdeleni" (Communication) from May 25, 1918.

The war created special situation in all areas. With great tension and as never before we follow the news from public life and the course of war, climbing of prices, and so on. This is because these phenomena deeply affect our family conditions. Today we cannot close ourselves in before these facts. They search us out right in our homes and family circles and draw us out into their whirl. Wishing it or not, we have to acknowledge their existence and more: every one of us has to struggle with them. So, even if in the background, we too join in the struggle, at least for maintaining our health and preserving our bodies. For us here this struggle is eased by the availability of well paid jobs. Factory worker can balance large price increases by the possibility of larger earnings and thus - if things did not get worse - today he could be still satisfied.

In the fight for today we often and easily forget about the struggles for tomorrow. Even the war will end one day. Surely, every one of us is yearning for that moment, but only a few realize that the peace will not immediately remove all our worries. The transition from war to peace economy will take more than one day. It will take a long time before the situation becomes settled and orderly, before we free ourselves from the mercy of haphazard fluctuations in public affairs. This transitional period will mean, for a man dependent on wages, a still new struggle to be waged to overcome the transitional difficulties towards the peace economy.

It is therefore necessary not to forget the tomorrow in our worries about today. Already now we have to take interest in assuring the possibility of large earnings in the future. How is the factory production going to pass through the transition, how is it going to be able to pay its employees - these are big question marks of the future. But there are still other questions. Many soldiers will return home, many who lost large incomes due to their absence; they will all want to share in the large earnings which were afforded to their luckier comrades who remained free from military service. And they will need these earnings because they will want to live, whatever their initial living conditions may be. What would happen if our factory, for whatever reasons and including the unfavorable industrial climate, had to curtail its production? How are we going to take care of those who would not be able to remain employed?

But there will be even further problems. There is no more pressing problem today than housing. Current situation, when people are piled up in lodging houses, receiving neither beneficial rest nor comfort and lacking even the most fundamental sanitary conditions, cannot be allowed to continue. Apartments will be needed. Can there be anything more beautiful than sunshine, warming up the air even in the shade, so that it pleases to remain and linger, as in a warm bath.

There will be also supply problems and all those small other worries which will weigh heavily upon us because it will not be possible to solve them as easily as before the war. In addition to the needs of the body there will be new needs of the mind, especially educational needs. Today, every even slightly rational human being knows that education influences not only his moral side, but affects his earning abilities as well. The means of education are libraries, lectures, theatres, concerts, etc.

All of this cannot be a problem for just one man, but for all of us who derive their incomes from the factory. Perhaps some have already thought about it, some perhaps even exchanged their views. There is no other way than to keep returning to these ideas more often and take an honest position towards them.

While thinking about our future economic and social situation, we find ourselves on the road where the interests of employees meet with the interests of the employer. The closer the meeting point, the more benefits to both sides.

Tomas Bata's speech to the workshop producing welted footwear on November 17, 1918

I would like to tell you today how important it is to work with enthusiasm and particularly in this department. The intention of my speech is to provoke such enthusiasm in you.

All of you who were working here already before the war are certainly well aware that we are manufacturing now a completely different kind of merchandise; this is a novelty even to those who were working here all the time, because during the war we were making military footwear which demanded much less skill and specialization that do today's shoes.

What matters now most is to learn the new production method and to learn it fast.